In the comments section Richard asked a good question in response to my last post. I wrote a brief reply in the comments, but I thought I’d flesh it out a bit as a blog post, because it’s an interesting topic.

The question is, ‘what’s the point of Tai Chi applications?’ Actually, to be fair, he was talking specifically about the one application video in my last post, not about Tai Chi in general. But personally I think you can extrapolate the question to include the wider Tai Chi universe, and that would be where I’d look for my answer.

There are plenty of videos of respected masters of various styles of Tai Chi running though the applications of their form movements and producing a series of very questionable applications that would require a perfect storm of events to happen for them to work. I don’t want to post them here because I think it would distract from the point I’m making, but look up ‘Name of famous master’ and ‘applications’ on YouTube and you’ll find them.

I really like the phrase “a perfect storm” to describe Tai Chi applications because as far as I can see, most (if not all) Tai Chi applications one would require a ‘perfect storm’ of attacker, positioning and timing for the application work. Therefore the one application video I posted previously is not particularly different to any other Tai Chi application video, at least to me.

That might not be a popular opinion, but I think it’s true.

Contrast this with a martial art like Choy Li Fut. I’ll choose CLF because it’s a kind of a typical Chinese Kung Fu style. It’s has some key techniques like Sao Choy – sweeping fist and Charp Choy – leopard fist and Pao Choy, a kind of big uppercut, Gwa Choy, a backlist, for example.

Here’s 10 of the ‘basic’ techniques that you find in CLF:

If you watch a Choy Li Fut form then you’ll see these 10 techniques crop up again and again, but each form enables you to practice them in different combinations:

Or check out the famous first form of Wing Chun – Siu Lim Tao, it’s a series of techniques performed very, very accurately so you can refine and practice them:

Now when you do those techniques in a form, you are performing a technique that would work exactly as shown. The only thing you need for success is to actually contact with an opponent and do the move correctly at the right time.

Tai Chi as a marital art just doesn’t work in the same way. We don’t have a toolbag of techniques designed to be pull out and used ‘as is’. Ward off is not a fundamental technique of Tai Chi – instead Peng, the ‘energy’ you use in performing ward-off, is the important thing. And I think this leads to a lot of confusion about what Tai Chi forms are.

So, if we don’t have techniques that exist in the same way as other marital arts, how are you supposed to fight with Tai Chi?

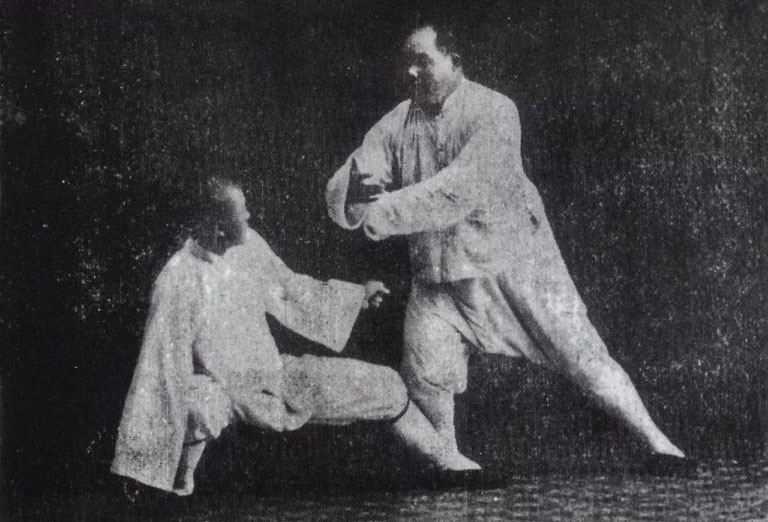

Tai Chi is a set of principles and a strategy that together make it a martial art. In a nutshell the strategy part can be summed up with the 5 keywords of push hands – listen, stick, yield, neutralise and attack. The principles cover how the body is used, resulting natural power derived from relaxation, ground force and a series of openings and closings expressed in the 8 energies. When the principles of Tai Chi are properly internalised you become something like a sphere, which can redirect force applied to you with ease and respond as appropriate. All these things are elucidated in the Tai Chi Classics.

Now that short description probably leaves a lot out, of what Tai Chi is, but at least it’s a starting point.

If that’s your goal, then putting emphasis on individual techniques doesn’t make much sense. Everything you do now exists in relation to an opponent, rather than existing on its own terms. The Tai Chi form then becomes a series of examples of how you might respond to specific attacks. In essence, it is a series of perfect storms, one after the other, put in a sequence that is long enough that you start to internalise the principles of movement and energy use. And obviously the strategy part requires a partner, hence why push hands exists.

I think that’s also the reason why Tai Chi forms are so long and slow, btw, so you internalise things.

As a final note, I’d say the jury is still out as to whether the Tai Chi way is the best approach to teaching people to fight. It’s interesting to note that a lot of martial arts innovators tend towards this same nebulous ‘technique-free’ style of training the further they get into their research into martial arts. Bruce Lee for example, was moving towards freedom and the technique of no technique in his later years – see his 1971 manifesto ‘Liberate yourself from Classical Karate’ for example. Then there’s Wang Xiang Zhai who created Yi Quan by removing fixed forms and routines from Xing Yi Quan and mixing it with whatever else he had studied. See his criticisms of other Kung Fu styles in his 1940 interview, for example.

In contrast a lot of the martial arts that have actually proven effective in modern combat events have turned out to be very, very technique based. Brazilian Jiujitsu, for example, is taught through very specific techniques. So is MMA. Karate, for all of Bruce Lee’s criticisms often does very well in competition against other more esoteric styles because it contains some no nonsense techniques.

Another factor to think of is that while Tai Chi may have those lofty goals of producing a formless fighter in its classical writing, it often isn’t taught like that in reality. One of the martial arts that Wang Xiang Zhai is criticising as having lost its way and become a parody of itself in that 1940 essay linked to above, is, in fact, Tai Chi Chuan!

So, as ever with marital arts, I think the answer is: it’s complicated.